post-internet

by Zlata Mechetina

Crisis of contemporary art, or a case of lobbying on a yacht, unpaid blond interns, and bold statements.

Hito Stereyl actively proclaims in Duty Free Art: Art in the Age of Planetary Civil War, that art is dead and serves as money laundering for the elites, ‘Public support swapped for Instagram metrics. Art fully floated on some kind of Arsedaq. More fairs, longer yachts for more violent assholes, oil paintings of booty blondes, abstract stock-chart calligraphy’. Not ideal.

This interrelated cycle of production and consumption of capital in the cultural form finishes off the era of pop celebrities with a bang. In this text I will talk about post-internet art as an alternative location of solidarity for micro communities and realisation of their online ‘cores’ (cottage, punk, dark academia cores per se). This cartography of commodity fetishism, labour, power, and science fiction sounds way more controversial and exciting than any painting could have potentially ever been.

No one is truly interested in contemporary art.

Neoliberal disillusionment – there are no hippies on the Internet.

The term ‘post-internet’ originated with early net art and web 2.0, marking a point when the Internet became business as usual. However,the original intention of the internet as an arena for openness and transatlantic borders, connecting everyone in one click. Cybernetics was introduced as a utopian technology to prevent another world war but it actually became a major instrument in neoliberal pacification. Within the climate of platform capitalism, it led to the slow, structural violence based on the exclusion of oppressed communities and extraction of libidinal resources (your desire to consume information and spend time online). Paul Preciado introduces this idea in Testo Junkie by focusing on bio-politics as a field of entanglement of war technologies and the entertainment industry, where users’ bodies and attention serve as resources for the extraction of capital. The idea of the web as a neutral space for the construction of identities and free exchange of information failed, and was never intended to succeed.

However, this interest in the libidinal economy of images, aesthetics born out of machines, and depression coming after an inhuman intelligence created a pool of artists working in an obscure but identifiable style, and I am going to talk about a couple of them (in an absolutely note-taking manner).

One of the pioneers of “the post-internet” is Jon Rafman, whose intervention into the private space of our bad romance with computers exists on the verge of uncanniness, dark comedy and pop-culture absurdism. A striking example of such is the short movie Still Life: Betamale (2013), featuring subculture and fetishist content from 4chan interrupted by still images of computer desks covered in bits of food and cigarette ashes and tapping into the aesthetic of flat screens and interfaces: “As you look at the screen, it is possible to believe you are gazing into eternity”.

He develops the theme of new ways of seeing in computer/drone vision using screenshots of eerie moments on Google Maps in The nine eyes of Google Street View (2008), overcoming the supposedly neutral gaze of street view photography, devoid of human sensitivities. The project is archived on Tumblr, http://9-eyes.com/, highlighting the status of the image on the Internet as both a representation and source material, which is subject to subsequent recombination and processing on different media platforms.

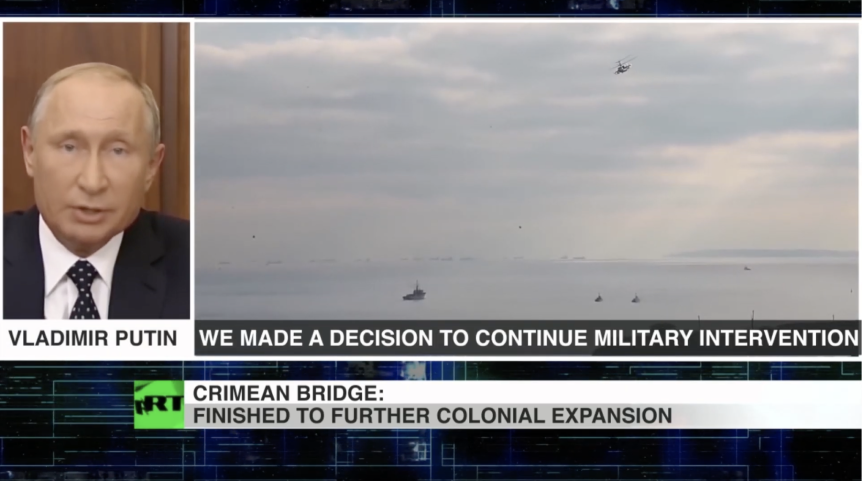

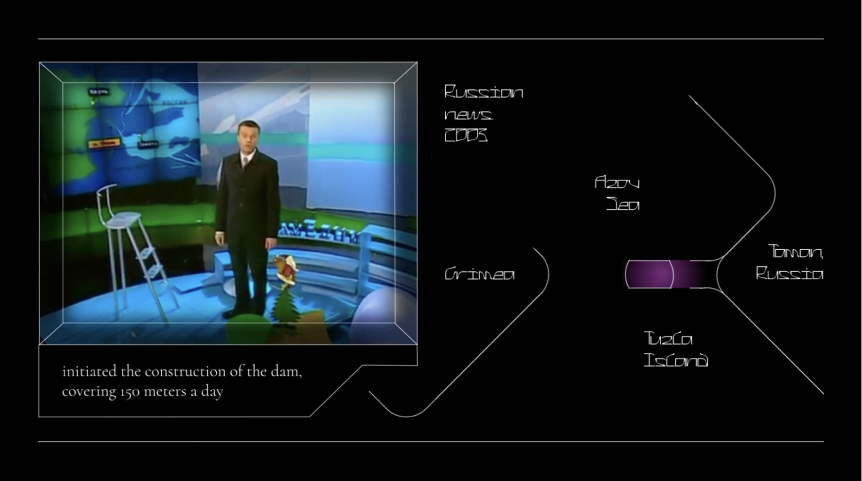

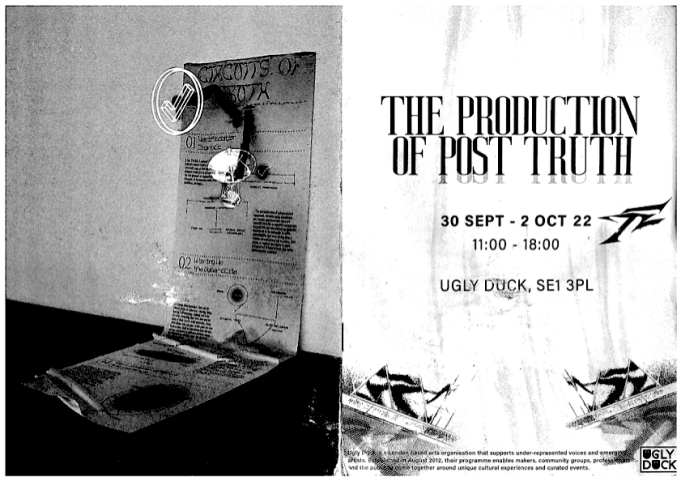

This leitmotif of violence pertaining to the web continues in Anna Engelhardt’s practice; she works within the post-Forensic Architecture framework, intertwining journalism, anthropology and contemporary art. She explores the violence of informational infrastructures in works such as Adversarial Infrastructures (2020), which discusses the colonial discourse behind the construction of the Crimean bridge, and Circuits of Truth (2021), which involves diagrams printed on textile, holograms, CGI, website, text, and can be seen as an aesthetically enchanting inquiry into the interfaces of polarised information loops: binaries of ‘true’ and ‘fake’. Most of her works can be interpreted as a form of map-making of Russian Imperialism and creation of spaces of heterotopia for smaller communities surrounding subaltern studies and new media researchers, as her practice creates a quasi video-game style visual language to present politically-charged research.

Post-internet as a post-creative space: norm core.

In The Language Of New Media, Lev Manovich argues that the modernist notion of creativity is overtaken by interfaces and platforms which curate and control the users’ choices and behaviour. Most people don’t understand how technology works, how those algorithms direct our understanding of reality, so the experience of reality itself becomes a dazzling mirage. In line with Manovich’s argument, artists have always had status quo, from shamans and magicians, Titian or Velasquez to pop stars, like Madonna or Kanye West. This mythological status would be achieved through acquiring a special relationship with technology (e.g fresco techniques, paint chemistry and later PR strategies and behavioural science) – but none of these characters are able to keep our attention span or surprise us more than people with direct control over technology, like Elon Musk. His status as both a myth, media, and monad would take over the unpredictability and grandiosity of any contemporary artist.

In this situation of the inflation of public relations and technologies of total design of personality and vibe building, an artist also acquires the alternative role of a tech-savvy educator, with a potential for spectators’ emancipation. In this case, I bring up the theatrical critic Viktor Vilisov, who turned away from physical theatre towards the format of ‘perfolectures’, presenting research in a digital lectorium. It follows the principle of “no face – no case” which carries less risks in the Russian political context. This digital environment anticipates and speculates on a kind of online existence that could be happening in a quasi-Metaverse space, and subverts the futures of it from the platform economy attraction to the alternative political resistence. His latest work, New War Technologies (2022), is a video essay about the theory of war and technologies of organised violence in four parts:

- The state of “liberal pacification”, when the violence permeates everyday life and becomes decentralised.

- The subjugation of scientific and technological spheres by the military; how automatisation affected biopolitics and triggered the development of autonomous weapons like drones, which gamifies the process of war and outsources the murders through civillian hands.

- The culture of fear: how it makes war possible; how this new type of public administration brings a constant potential of death; how it is gendered, what is sovereignty and borders, and how macro fear functions in the neoliberal regime.

- The last part focuses on traces of war in cities and human bodies, more precisely on the anthropology of war and death . What is “invisible death”, what kind of bodies are mournable; how to look at images of extreme violence. And Viktor finishes with the following question: is humanity doomed to war, or has war always been with us?

This investigation into the immateriality of fear, violence and their digital presence proves the status of post-internet art as a tool to find faults, absences and places of solidarity in social studies, literature, and philosophy by pin-pointing the so-called intersection of art and technology, and showing how tiny and conceptually unexplored this area is. As it cannot be written down under the social science/anthropology research label, such works become a sort of map-like objects, you will need to look at its references and navigate yourself within critical theory and (mostly) speculative realism. This endeavour carries certain ethical responsibilities in being a kind of a gentle monster, staying both critical and caring for its allies. Seducing the audience into critical infrastructures through the employment of teenage dream sci-fi or video game aesthetics.

Connectivity: aestheticisation of infrastructures.

The term itself, ‘online’, etymologically anticipates the imagery of webs and connections. The in-between status of post-internet art between physical and digital place serves as a trigger for rethinking the ways people create culture and co-exist with other species, as the cyberfeminist scholar Donna Harraway discusses in MIT’s Journal of Design and Science. Harraway argues how essential it is for social organisms to play. Haraway defines play as a ‘metacommunicative signal that loosens meaning from functionality’ for the sake of potentiality.

Apocalyptic imagination becomes a logical and productive response to the personal inability or refusal to become a professionally literate tech person or a programmer and making a choice of taking an outside position of a historian or tech anthropologist. This kind of mystic fiction can be found in Most Dismal Swamp’s practice, a ‘mixed-reality biome, an art platform, a multi-scalar mystic fiction, a forecasting laboratory, a long tail, a transitional ecosystem,’ whose works display shock of disillusionment - katabasis ** (a ritual descent across worlds in order to materially and contingently affect and infect their current order, exposing computing to what is not yet computable).*

His focus is on the anonymous swarm of the internet-underground of Reza Negarestani, Pussykrew, English Heretic, speculative turn, and swamp inspiration, oscillating between punk culture and expensive vfx. This materialist literacy within a contemporary marginal topography makes sense out of the digital simulators and stimulators through visual seduction, atrocity, and rage vs a matter of strictly functional constitutional design.

It is exactly the commercial design supporting the performativity of the web which serves as a capital extracting machine from human habits, emotional experiences and neural activities; such obscure and nocturne intervention and (re-)construction of pop-culture confuse both the audience and algorithms (which is exactly why post-internet art remains niche). An example of this is Most Dismal Swamp’s most recent short movie MUSH,which explores the simultaneous tech-inspirations of ‘gangcrafting’ and subcultures of online territories, reinforced by offline organisation and social balkanization. He creates a greenhouse of fluidly draconian Ts&Cs, gamified feedcrafting algorithms, algo-culture, speculation of the reality to capture the fragile communities in platform-mediated circumstances.

The most adequate way to describe post-internet art without falling into eco-political depression is the development and employment of tools of care, storytelling, play, and activism. For instance, MUSH focuses on the emergence of phenomena such as ‘astroturfing’, which is when communities seek and embrace alternative, private, or ‘off-grid’ spaces but in a tech aware and media literal way.

Conclusion: ars longa, vita brevis.

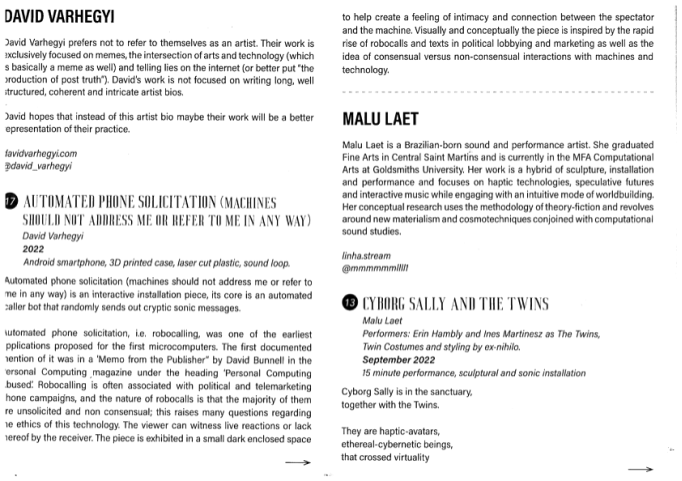

Even though I have focused on the more political/social takes on the post-internet, there are more branches, such as neo-paganism, exploring the relation between spirituality and machines. I will bring up David Varhaegi, whose works are focused on this intersection of arts and technology, memes, and exploration of the sublime in offline subculture and manifesting various cyber-identities manifested through physical objects.

One of his most recent works, Automated phone solicitation (machines should not address me or refer to me in any way)(2022) is an interactive installation piece with pre-recorded bot calling messages. It alludes back to one of the earliest forms of media archeology, the robocalling, often associated with political and telemarketing phone campaigns. The majority of them are unsolicited and non consensual; this raises many questions regarding the ethics of this technology. The piece was exhibited in a small dark enclosed space to help create a feeling of intimacy and connection between the spectator and the machine, conceptualising the idea of consensual versus non-consensual interactions with machines through media archeology, technologically advanced laser cut plates, and hyperpop remixes playing in the background, delving the viewer into the realm of media archeology and pop culture.

At the end of the day, suddenly, our magicians are hackers, digital restorers and programmers. Dark matter of the art world and invisible labour of the white cube steps out. Let’s gatekeep the Pollockian modernist trope of the celebrity artistic genius, there is no time and need for that (you can still be delirious enough purely for Instagram reasons if your parents own a gallery or have a hedge fund to get you a booth in Frieze or whatever but honestly it is not even that fun). Most creative decisions would be in solving practical and infrastructural problems.

References (more like a reading list):

Berman, Marshall. 2010. All That Is Solid Melts Into Air. New York: Verso.

Knapp, Ivan. 2020. A betamale is being beaten. Object. 21(1)

Manovich, Lev. 2000. The Language Of New Media. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Mckenzie Wark. 2020. Sensoria: Thinkers For The Twentieth-First Century: Thinkers For The Twentieth-First Century. London, UK: Verso Books.

Mladentseva, Anna. 2022. Responding to obsolescence in Flash-based net art: a case study on migrating Sinae Kim’s Genesis, Journal of the Institute of Conservation, 45:1, 52-68.

Preciado, Paul B. 2017. Testo Junkie. New York, N.Y: Feminist Press.

Steyerl, Hito. 2018. Duty Free Art. London, UK: Verso Books.

Freider, Ester. 2022. “ANOTHER WORLD”. The Weekly Centaur.Substack.Com.

Haraway, D., & Endy, D. (2019). Tools for Multispecies Futures. Journal of Design and Science.

Viktor Vilisov - New War Technologies